It is almost certain that the user manual of any new vehicle you purchase will stipulate a running-in period usually of 1,000 miles or more. Why is this, and is it even necessary with modern engines and the advance in materials and machining techniques?

I’ll answer the second part first – No, not in my professional opinion. I’ll get onto the “why” later.

So what do I mean – no? Am I mad? Well, only on the first tee of a golf course with a driver in my hand. It’s incredible how one loses their senses in this situation – only a golfer will understand this madness. But I digress; let me explain.

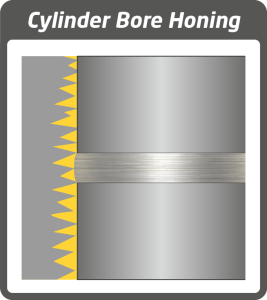

Going back a few decades, cylinder liners underwent a single-stage honing process that left a crosshatch pattern on the surface of cylinders or cylinder liners. Sharp, jagged edges created by the newly honed surfaces then needed to be removed or smoothed to provide an optimum seal between the piston compression rings and cylinders.

This was best achieved with lower quality, usually mineral-based, engine oil allowing the piston rings to bed in against the cylinder, thus creating a tight seal. This bedding in process, basically “controlled wear of engine components,” included a gradual increase in load and revs on the engine over a period of running hours and miles. This was essential to deliver a good seal and cylinder compression and limit engine oil consumption. The engine oil would be replaced with a higher quality semi or fully synthetic oil with friction modifiers designed to lower friction and reduce further wear.

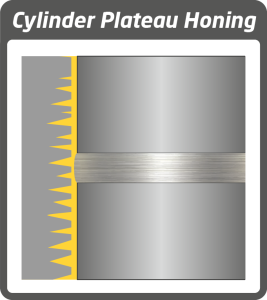

It is much different now since manufacturers introduced a final stage honing process. Referred to as a plateau hone, this finishing process simulates most of an engine run-in by removing the sharp, uneven ridges created by the primary honing process. It guarantees an almost perfect seal from the outset or at least very close. It also enables manufacturers to use high-quality synthetic oils from the factory without the need for running-in oil. Therefore, any final running in should be completed promptly and not over 1000+ miles, with a risk of bore glazing resulting in reduced power loss and potential excessive oil consumption.

So why do manufacturers still insist on a lengthy running-in period?

I have spoken to numerous professionals on this subject, including a Metallurgy Professor who has worked with vehicle OEMs. There is no definitive answer, but here are my conclusions:

1. Manufacturers may be using the running-in period as mitigation against minor machining tolerance issues from the manufacturing/assembly process, which may then resolve through other bedding in. However, I believe any underlying fault would likely surface at some point regardless of how an engine is run in.

2. Even though the engine may not require as much bedding-in, other components such as the drivetrain (manual clutches, auto clutch packs, differentials, etc.) may do so. Then there are brake pads and discs, not forgetting those brand-new tyres. You get the idea.

3. User orientation. Being new, the car is likely to feel very different, and driving more cautiously gives the user time to become more accustomed to the vehicle.

4. Finally, the £ – applicable to BMW M-cars. Every M car owner knows the importance of the 1200-mile running in service that requires an engine oil and filter change as a minimum. However, even BMW acknowledges that the factory fill oil is the same specification oil used for the 1200-mile run-in service. Oil analysis taken from the initial 1200 mile period has shown minor material wear or at least not enough to warrant a change after 1200 miles. Go figure!

Now we look at the other end of the spectrum. There is a consensus that owners of brand new vehicles should drive them “normally” from new or drive them like they stole them! This is also incorrect. Even though a plateau hone has done a lot of the hard work for you, there is still some work left to do.

This is how I “bed-in” my new cars; none of them have ever required oil top-ups between services. These include high-performance vehicles such as Audi S and RS models and BMW M cars.

I usually complete the engine run-in within 200 miles, with the first 50 miles being the most critical.

1. MOST IMPORTANT: Bring the engine to FULL operating temperature through everyday driving, allowing the engine to rev freely. Do not lug a brand new engine or leave it idling for an extended period! Where possible, use manual shifting with automatic transmissions to stop it from holding on to high gears and lugging the engine.

2. In the lower gears, particularly 2nd and 3rd, and where safe to do so, accelerate moderately to approx. 2/3 of the rev range and let the vehicle slow down using the engine braking rather than the foot brakes.

3. Repeat this process, slowly increasing the amount of throttle to increase the accelerative effort/engine load. Then move up to 4th and 5th gear for vehicles with transmissions with seven or more gears. Again, only when safe to do so and remaining respectful to other road users. Drive the car normally for a short while, allowing the engine to cool.

4. Repeat steps 2 and 3 but increase the revs by approximately 1,000 each time, building up the load and gears until you eventually reach full revs in mid-range gears. It is not necessary to achieve full RPM in top gears to bed an engine in fully. It is also unsafe on a public road. Full throttle in the mid gears to full RPM and full throttle to a safe RPM in the upper gears is sufficient. It is not an exact science, and 50 miles is sufficient to give you an idea of how much running in is required.

5. For the remaining 100-150 miles, drive the vehicle normally but occasionally running a full-throttle run in lower mid to mid gears using the natural engine braking to slow the vehicle down. The engine should now be entirely run in.

I hope this proves helpful. Please read our article “Eradicate Bore Glazing” HERE to correct any existing bore glazing condition.

categories

categories