When examining the field of products, services, and techniques that promise to increase MPG, you find a confusing minefield, at best. There are chronic sceptics on one side, loyal devotees on the other, and indifferent observers in between. Unfortunately, this has come from a long history of ignorance and misleading advertising. The dilemma for most is “who is right and who is wrong?”

Two other main questions also might come to mind:

1. How do you know if the advertised MPG increase will be achieved?

2. Why are there such inconsistencies regarding product results, ranging from spectacular to absolute zero? Why such a significant variance?

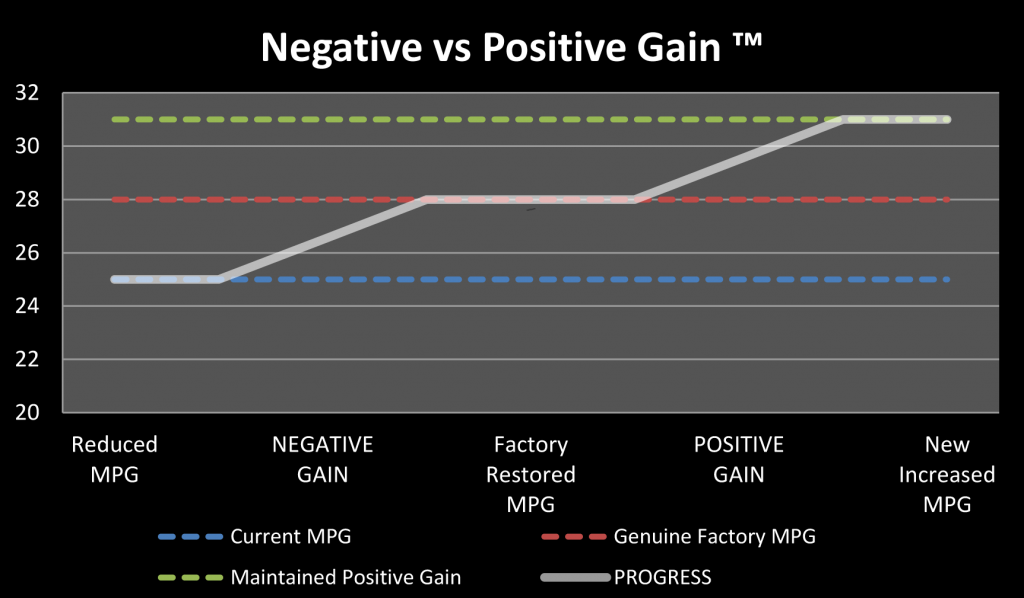

When we service fleets, we combine our knowledge and experience to simplify the process for operators. Firstly, let us explain the type of gains available and the results you can expect to achieve. To best explain this, we would like to introduce you to the concept of Negative versus Positive MPG gain.

Negative Gain is the process of restoring engine economy and efficiency back to factory levels, or more accurately, how it was when it left the manufacturer, except with an engine that is now run-in. These are not the factory-published figures regarding performance, but moreover, the actual performance that is possible from an engine that is run-in, deposit-free, and operating at full efficiency in real-life conditions. This is engine efficiency restoration.

Positive Gain is the process of improving the standard MPG or performance of an engine that is deposit-free and running efficiently on standard pump fuel and lubricants, as recommended by the manufacturer. This is engine efficiency enhancement.

Virtually all fuel and engine additives suppliers claiming 10%, 15%, or 20%-plus improvements in MPG rely heavily on the Negative Gain factor. The increased economy claims are based on the assumption that the fuel system has accumulated deposits and that the engine is experiencing a reduction in fuel economy and performance as a result.

This is very important. The reason for such inconsistency is that there are many variables in play. One vehicle may have a considerable reduction in fuel economy or performance (due to fuel system or engine deposits), while another has virtually none. Also, different engine designs respond to deposits in varying ways. It is really that simple. The majority of gain you tend to see, however great or small, is negative gain or performance and efficiency restoration. Unfortunately, negative gain or efficiency restoration potential is challenging to predict.

This part of fuel and oil additive marketing is particularly troubling, as it can lead to unrealistic customer expectations. We believe it is misleading to make claims about MPG increases on the assumption that the fuel system and/or engine have accumulated substantial deposits. Of course, such claims are always caveated with increases “up to” a certain amount.

So how does the negative and positive gain theory work?

Negative Gain (Economy & Performance Restoration)

Assuming that the mechanical condition of an engine is good and that all its electrical components and respective sensors are operating correctly, there are three ways to restore lost MPG.

1. Fuel system cleaning. This involves using a professional cleaner to remove any benign or debilitating deposits from the fuel system. It also includes any remedial work to remove biological or non-biological contamination within the fuel or fuel system. This restores the correct fuel flow and atomization of fuel into the combustion chamber.

2. Carbon Removal. This is the process of using professional cleaners and combustion modification technology to remove carbon build-up from the combustion and post-combustion areas of the engine. These include emission control components like the exhaust gas recirculation system (EGR), diesel particulate filter (DPF), etc.

3. Compression restoration. This is the process of restoring any lost engine compression by using a professional engine oil flush or lubricant-based cleanser to remove deposits from the pistons, piston rings, and cylinder bores.

Depending on which of the above apply and assuming the correct products and processes are employed, virtually any engine can be restored to optimum efficiency and performance. The only notable exceptions are when an engine, or any of its periphery parts, are mechanically worn, degraded, or failed. Even then, various technologies and processes exist to restore minor wear.

Positive Gain (Economy & Performance Enhancement)

Again, assuming all being equal and that an engine is in good working order, there are five ways to increase efficiency and performance above the standard factory figures.

1. Friction reduction. This involves using specialist products and techniques to reduce friction to levels lower than that available from conventional oils and lubricants. Other benefits can include greater protection against reduced component wear and lower maintenance costs. This can be applied to engines, transmissions, differentials, wheel bearings, and so on.

2. Fuel combustion modification. This includes the continuous use of professional chemistries to improve the combustion efficiency of the fuel, resulting in greater fuel economy, performance, and a reduction in exhaust emissions. Such products can also prevent fuel degradation, protect the fuel system, and control deposit build-up, thus removing any future need to use products to restore lost performance.

3. Engine retuning (software). This is the process of altering the engine control unit (ECU) or how the ECU manages fuel injection, ignition timing, and other engine control parameters. This can provide more efficient power and torque delivery throughout the rev range, reducing fuel usage.

4. Engine retuning (physical). This includes the physical modification of engine components such as adjusting intake manifold air-flow dynamics, altering the exhaust system or DPF, and so on.

5. Other modifications. Making other pragmatic modifications that are widely known, such as optimising tyre pressures, improving aerodynamics, reducing unwanted weight, altering driving style, etc., can also improve efficiency.

Positive gain can manifest itself as additional performance (as measured in horsepower and torque), an increase in fuel efficiency, or a combination of both.

Testing Protocols:

We specialise in the development of bespoke MPG testing protocols. With any test, whether a single consumer vehicle or a fleet of heavy goods vehicles, it is important to set objectives and correctly plan how to achieve and measure them.

Below are some contributory risks and variables that must be considered when developing a comprehensive test plan. Please note that we were advised against revealing this information as it would undoubtedly be copied and reused by other companies selling fuel-saving additives or devices. However, if it helps to restore some integrity to the field of MPG testing, then we believe this benefits us all. Whether you sell fuel-saving technology or are looking to test and buy fuel-saving technology, let’s please restore some integrity to this field.

| Risk | Mitigation / Containment | |

| 1 | Length of the test is too short. | It goes without saying that the more test data available, the easier it is to discern positive, neutral, or negative results. |

| 2 | Lack of availability of historical test data and seasonal differences. | It is of paramount importance that historic baseline data is available. If not, this should be captured first. Also, take into consideration the seasonal variations. For example, if you are conducting a three-month test between April and June, it would be advantageous to have baseline data for the same months in the previous year and the months of January to March immediately before the test. You would be surprised with the variance of data between seasons. |

| 3 | Inaccurate MPG monitoring techniques. | The most common are on-board monitoring and manual calculations. Where possible, use both monitoring techniques. Telematics that includes average speed is also extremely valuable as it will help validate or invalidate MPG figures. If the average speed for a vehicle increases during a particular month, then the MPG would be expected to increase by default and vice versa. |

| 4 | Varying climatic conditions. | Weather can have a profound effect on results, and not just temperatures. Wind can affect drag; rain can affect grip, etc. A combination of controlled and real-life tests can mitigate this. |

| 5 | Varying traffic, routes, and loads. | Variances in routes, traffic, and loads can affect results. Choosing the most consistent routes with consistent loads in low traffic periods and a combination of controlled and real-life testing is the best bet, albeit not always possible. |

| 6 | Driver inconsistency. | Where possible, the same driver should be used. Otherwise any change of driver must be factored into the test results. |

| 7 | Varying vehicle history and condition. | Even vehicles of the same type and engine are different and can respond differently. Pick both a poor performing and good performing vehicle. It is important to understand that results are only applicable and valid to that particular vehicle/engine combination. |

| 8 | Fuel inconsistency. | Different brands and types of fuel (including seasonable blends) can affect results. Where possible, the exact same fuel should be used throughout the test and during any pretesting. |

| 9 | Poor accuracy with administering treatments. | How treatments are administered is important. For example, treating the fuel at bunkered storage mitigates the risk of incorrectly applied ratios when testing fuel additives. Automated dispensing systems are also an alternative. |

| 10 | Driver awareness affects results. | Blind testing always provides the most accurate results unless trust in the driver is assured. If the driver is aware, then also make them aware during the pretesting (baseline) stage. This can ensure that the driver will not significantly change the driving style during testing. |

| 11 | Fuel or additives theft. | Unfortunately, this does occur. There are ways to identify and mitigate this risk. However, it would not be appropriate to list them here. |

| 12 | Lack of test data. | What to test (mpg, power, torque, emissions, oil quality, wear, etc.) is fundamental to understanding the benefits of any given product(s). Simply, the more data, the greater the confidence in the decision-making process. |

There are other minor factors that we won‘t go into as they apply more to controlled testing, such as the effects of ambient temperature on fuel density and so on. However, the above twelve points will serve you well.

We make our clients fully aware of the common pitfalls and underhand techniques that some companies use. For example, a common tactic is to advise the client to notify the driver that a test is being conducted. The driver is then aware that his driving is likely to be scrutinised and, as a result, drives more cautiously and ” efficiently. ” The client then witnesses a tangible increase that has little to do with the prescribed treatments but is instead from an improvement in driving style by the driver.

Another tactic is to convince the client to pick their worst-performing vehicle for testing. This, of course, increases the probability of more outstanding results. The client then becomes blinded by negative gain results that cannot be reproduced on their other, better-performing vehicles. Ideally, you should test average-performing vehicles or the worst and best-performing ones in the fleet.

The key is to produce a test protocol that mitigates or eliminates as many variables as possible. This will help ensure accurate test data, which, in turn, enables the client to make informed decisions as to the actual ROI on particular treatments or processes.

If you require more information or a no-obligation consultation on MPG reduction or engine cleaning, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Yours,

Andy Archer

Managing Director

Energy and Maintenance Saving Consultant

categories

categories